Last week I (virtually) sat down with Dustin Growick, Audience Development and Team Lead for Science at New York-based tour and consulting company Museum Hack, to have a transatlantic Skype chat about engaging with millennials and challenging the traditional museum experience.

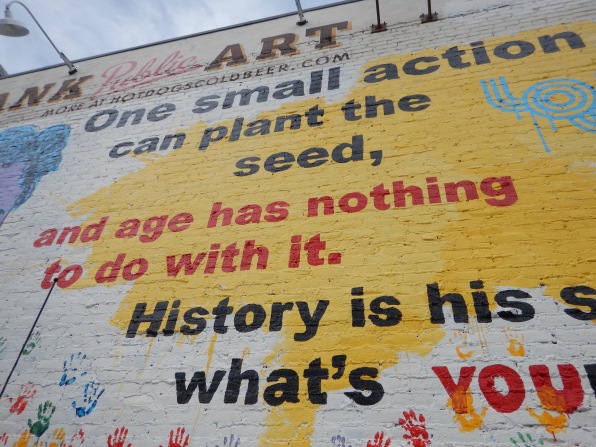

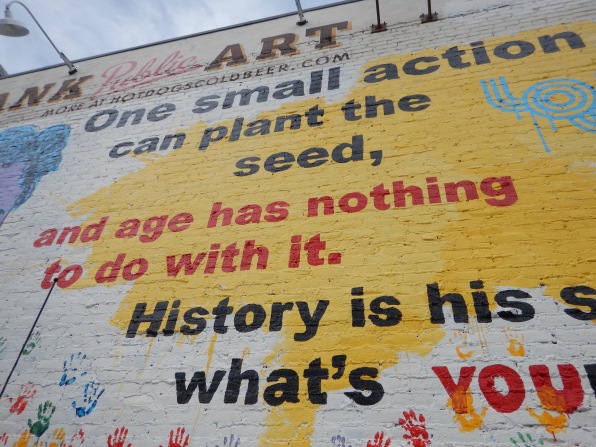

Public art in Austin TX, 2015. Author’s photo.

I must admit that I initially had a few reservations about the company’s unconventional approach to museum education. While I’m a big supporter of visitor interaction and play in museums, as an outside observer I found some of Museum Hack’s themes and strategies somewhat superficial. However, after drilling down into Museum Hack’s approaches and philosophy, Dustin started to convince me that they are making traditional museums more welcoming and accessible to new audiences.

“This is a place for you just like it is for everyone else.”

As a lifelong museum visitor and heritage professional, I’m not the target Museum Hack audience (and if you’re reading this super nerdy museum blog, you probably aren’t either). I learned from this interview that Museum Hack tours aren’t for people like me, they’re for the millions of individuals who don’t want (or know how) to engage with art, artefacts, and exhibits. Museum Hack programming may seem silly or frivolous on the surface, but it can act as a crucial gateway that many museums have struggled to provide for themselves. My chat with Dustin showed me the valuable role they can play to make people feel more comfortable in museums.

Here is an abridged version of my interview with Dustin, with minor edits in the interests of brevity and clarity:

Ashleigh: Could you explain in a sentence or two what Museum Hack is?

Dustin: Museum Hack is a band of renegade tour guides, but really young, really enthusiastic, curious, passionate New Yorkers who use the Met [Metropolitan Museum of Art] – well not just New York anymore, we’re in D.C. and San Francisco now – we use the museums as cultural playgrounds to lead 2 hour museum adventures. I don’t even call them tours, I call them “2 hour museum adventures” because they definitely subvert the expectations of what a museum tour would be. I think the primary two things that we focus on are:

- Telling tremendous stories. We focus on how you craft incredibly fun and engaging narratives that show people the points of personal relevancy that get them excited and bought in.

- We make sure everyone who comes on our tours gets to actively participate in the creation of the meaning of their experience. We try to give people agency. We recognize that if you are not already bought in, we want to give you some sort of agency to experience a place on your terms. So we do a lot of games, activities, and challenges that are interactive and social and allow people to take some ownership, so it’s not simply a unilateral delivery of information for two hours.

A: What do you do at Museum Hack?

D: I’m part of the Audience Development team, so my role – in addition to still doing tours at the Museum of Natural History and the Met 2 to 4 times a week – is talking to museums around the world about how we can work with them to help them get new audiences. We do that through professional development workshops…we work with museums to develop Young Professionals programmes, we work with them to reimagine what their programming and events look like…we’ll do talks and presentations as a “re-fall in love with your museum” type of thing, really anything that helps people rethink what the museum experience is and ultimately get new audiences through the door.

A: Very cool. So from what I can see, Museum Hack has a really strong focus on millennial audiences and getting them engaged with museums. Why do you focus on millennials, and what tactics do you use to engage them specifically?

D: We focus on millennials first because we are them. Everyone who works at Museum Hack loves museums, and I think a lot of us recognize that these are places that our friends aren’t going, and we don’t see a lot of people our age there. Museums do a great job engaging families, school groups, older people…if museums don’t do something now and start courting millennials, we’re the next generation of donors and docents, so we want to get people involved now.

Millennials are inundated with choices, so its not like the museum is just competing with going to a movie or an amusement park – you’re competing with Netflix, with hundreds of thousands of options of Yelp. We want to show people that this is a place that relates to their life, and we do that by giving them agency, and allowing them to create meaning within the experience…I think in most museums there’s still a unilateral delivery of information. If I’m not already really excited to learn about Byzantine brushstrokes, then I’m not going to come. We have to entertain and engage people first before we get to the point where they’re actually going to be bought in for longer term learning and love the museum. We do that by being fast-paced [and] through smart use of smartphones. Smartphones are a great tool for getting people to not only just socially interact more between each other at the museum, but also look closer at the art…millennials are going to have their phones quite literally in their hand at almost any moment, so how do you use that as a tool to get them excited and bought in?

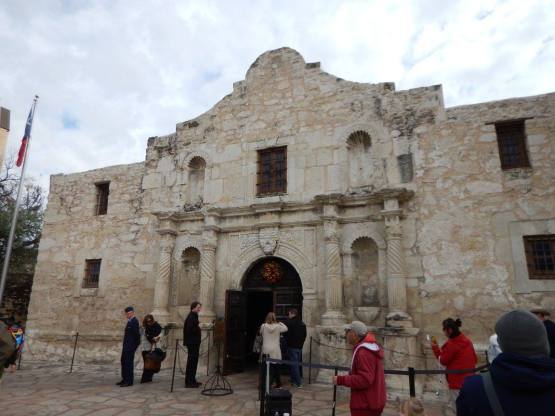

Rijksmuseum, 2015. Author’s photo.

A: Do you ever have issues with different museums you work with about using smartphones and taking photos in the galleries? Certain museums are still quite strict about photography policies.

D: For the most part the museums we work with recognise what we do and how we do it…Any museum educator or docent wants people to come and forge an immediate connection with a piece of art…and think long and hard about what this artist meant, and how they feel about it. If you tell someone to find something and go do that, it’s a non-starter. If you tell them to take their phone and find the weirdest looking face in this portrait gallery, take a picture of it, and come back…we pair people up with a thing called “Matchmaker,” where they make up the epic love story that brought these two people together. This is silly and ridiculous, but now these people are interacting; they’re both talking about different pieces of art; they have to look closer not only at the piece they chose, but also at something someone else chose; and, they compare and contrast and make up a story about it. Now they’re engaged, and relating their lives to the art…it starts with meeting people at their own likes.

A: In your video on the Museum Hack website, you talk about leading tours that are “subversive adventures”. How do you make your tours subversive?

D: We subvert expectations of what a tour even is. We start that from the very beginning of the tour…everyone on the tour puts their hands in the middle, like a sports team, and we do a cheer….right from the get-go you’re setting the tone that we’re all in this together and this is going to be a social experience…we’re going to have a ton of fun, we’re going to do this weird thing together…it’s not going to be what your normal tour looks like. Adults don’t play games in art museums, but we use games ultimately as teaching tools.

Another way we subvert expectations is to tell the stories that either you won’t hear on tour, or you are specifically not allowed to hear on tour. We’re going to talk about the scandalous back stories behind the art, or the relations that happen between the people that made it, or why a particular curator has done this.

A: I find children are often given lots of opportunities in museum programming to engage with material in a way that is fun and interactive, but for adults it doesn’t happen that often. It sounds like from the start of the tour, you’re giving permission for adults to actually interact and have fun too.

D: Exactly…I think that’s one of the things that makes it work. We subvert that – whether it’s real or perceived – boundary to engage. “I don’t know anything about art, this is a very serious historic place, I have to leave my phone inside” – no, this is a place for you just like it is for everyone else. You can have fun in here, you can loosen up, and have a good time.

A: In a TEDx talk last year, your founder Nick Gray talks about tours needing to be more about storytelling and less about art history. Is there a risk of cherry-picking certain factual information because it’s more juicy or interesting, instead of presenting things in an accurate way?

D: Everyone cherry-picks, if you’re a docent you choose what you’re going to talk about. We cherry-pick what we find to be the most fun, salacious, hidden stuff because we want to tell mind-blowing stories to get people really excited. That being said, we also understand because we’re outsiders, it’s very important for us to be factually correct and not make anything up because we could get shut down very easily…or lose our credibility. During the training we have people fact-checking our guides…we focus a lot on making sure the things that are being said are true, but we absolutely cherry-pick.

A: You mention doing fun, quirky things and covering salacious material in your tours. Does Museum Hack ever deal with sensitive content where it might be difficult to present it in a fun and lighthearted way?

D: Yes, but not often. We know what the product we are selling is, and people know generally what they’re getting into. We couch this as a fun, crazy, wild museum adventure, so we’re not going to generally talk a lot about really heavy topics because it’s just a downer. That being said, sometimes someone will ask questions or a conversation will turn that direction…it’s not something we choose to talk about, because we choose to make it a fun, engaging time. Talking about slavery for half an hour probably isn’t going to get people that excited…there’s a time and a place for that conversation, and I don’t think it’s during one of our tours.

When we do choose to tackle a tough subject, we go headfirst into it. One of our staff members put together a “Bad Ass B*tches of The Met” tour. It’s all about how there are very few female artists on display here…we’ll talk about appropriation…we talk a lot about provenance of art, and who really gets the credit and where it comes from. Just because a curator put something somewhere doesn’t mean that’s the most important thing or that it’s the best thing to represent whatever they’re trying to represent. So we’ll definitely tackle those topics.

A: I’ve been in many museums myself where I don’t always agree with the info boards or interpretation. Do you ever get any pushback from your host institutions if you’re talking about their curation in a different way, or do they welcome it?

D: I’m not aware of any pushback…and I’d like to think of ourselves not as competing with them. The tours at The Met and the Museum of Natural History are amazing, they’re definitely for a self-selected group. We’re trying to reach a different group. There are times and places for both. I think they recognize that too.

The Getty Center, 2011. Author’s photo.

A: Right now you guys do tours in the United States in a few major cities. Do you have any plans to expand outside of the U.S.?

D: There’s been a lot of talk about London, because obviously a lot of people would love to make that happen. Our next stop is Chicago…it’s on a city-by-city basis. We need cities that have large museums with large visitor bases from which we can draw ticket sales. Honestly that’s the reason I love to do these [professional development] workshops, because now I get to go to small cities and small museums where we could never set up shop, and share around what we do. Hopefully they can infuse what we’ve found to be best practices into their practice.

A: This is probably a really tough question to answer because it’s hard for me to answer, but if you had to pick a favourite museum that you enjoy as a visitor, what would it be?

D: One of my favourite art museums is the Dia:Beacon. It’s an old Nabisco cookie and cracker factory about an hour north of New York City. It’s been converted into a contemporary art space, and it’s awesome. As far as science museums go, the California Academy of Sciences hands down; it’s a science centre, a natural history museum, a zoo, an aquarium, a planetarium. The roof itself is a living roof…full disclosure that’s after the Met and the Natural History Museum here in New York, obviously.

A: Of course, that goes without saying. The last question I have for you is: how did you get into Museum Hack? What’s your background?

D: I was working at the New York Hall of Science, and I met…the first two guides of [Museum Hack] at a New York City Museum Educators Roundtable, and I heard about what they were doing at The Met. I asked why they weren’t doing this across the Park at the Museum of Natural History. They said they’d thought about maybe one day going across [Central] Park and I was like, you know what? I want to make that happen. So I created the tour programme we have over there from scratch…two years later here I am, still doing tours there but now I get to go to museums all over the country and all over the world. I’m going to Australia in October. Ultimately we’re in this because we f*cking love museums, and we want everyone else to f*cking love museums too. It’s been a crazy, wild two and a half years…it’s been a fun ride.

Thanks Dustin for giving us a great introduction to Museum Hack – we really love museums too.

British Museum, 2015. Author’s photo.