During a recent trip to San Antonio, Texas, I had the opportunity to visit a few of the eighteenth-century Spanish Catholic Missions along the city’s Mission Trail – including the famous Alamo battle site and shrine. The Mission sites were a pleasure to stroll through on a sunny Texas afternoon: exceptionally well-maintained and restored, easy to find, and completely free to visit. They are certainly a must on any tourist’s checklist.

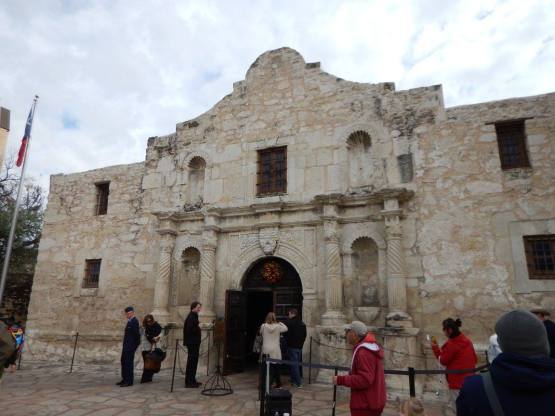

Mission San Antonio de Valero, more commonly known as the Alamo.

These missions were first built as symbols of Spanish culture, religion, and imperial power during the period of European expansion into the Americas. They also represented the devastation of traditional cultures and ways of life for many indigenous groups . As I enjoyed strolling through the tidy lawns and well-preserved churches of each mission, I couldn’t help but think of the fear and suffering these walls must have witnessed in centuries past.

However, this narrative was not reflected in the numerous interpretive panels I encountered at each site. Large, illustrated, approachable signs placed strategically around each site gave introductions to the history and work of each Mission. The text detailed key dates and names in each site’s development, and an overview of the religious and administrative work that happened there. Yet I was disappointed by the lack of information about the negative impact Spanish imperialism had on indigenous communities; the interpretive signs described the “religious lessons” and “accommodations” provided to the local people in benign, positive terms. There was no mention of loss of land, disease, and oppression, nor the erasure of local languages, traditions, and beliefs that were an inherent part of European invasion and colonization of the Americas.

Mission Concepción, San Antonio. Dedicated in 1755.

According to information on the National Park Service’s own website, many indigenous people were compelled to enter the Missions, convert to Christianity, and abandon their traditional ways of life in order to survive the changes wrought by Spanish expansion into their lands. I am by no means a Texas history buff, but such phenomena are relatively common in the histories of empire. Certainly life wasn’t bad for all those who lived in and around the Missions, but I had hoped the interpretive signs would paint a more realistic (and challenging) picture of what those institutions meant for the local populations. I have a high regard the National Park Service overall, so I was especially surprised by this apparent evasion of difficult historical narratives.

There are many examples of museums confronting difficult and disturbing histories head on. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. has famously illustrated the power of museums to bring awareness and empathy to extremely painful and complex stories. The International Slavery Museum in Liverpool is another excellent example of a museum that explores the connections between historical wrongs and modern inequalities.

I am a European Canadian living in Vancouver on unceded Aboriginal territory. I am conscious that the citizenship and the lifestyle I enjoy are the result of European colonialism and the displacement of indigenous cultures and societies. Yet for many years, I did not draw a personal connection between my country’s colonial past and my own life. My family came to North America from Britain at the end of the Second World War, centuries after the first colonists arrived in this land; a fact I once thought exempted me from any link with the decimation of many indigenous cultures. I now realize that those earlier colonial atrocities paved the way for my own relatives to emigrate easily from Britain to a former imperial holding, without needing to learn a new language or even swear allegiance to a different monarch. European colonization and its lasting impacts on indigenous communities are a part of my personal history and identity, as they are for North Americans of all backgrounds.

To use Aboriginal scholar Dr. Susan Dion’s term, no one is a “perfect stranger” to indigenous history and modern issues. Though difficult, museums and heritage sites have a responsibility to confront these distressing topics and challenge visitors to understand their own connections to them.

Mission San José, the largest of the San Antonio Missions. It was completely restored in the 1930s.